Wolf Warrior II: Subtitle Translation and Transcreation of China’s Identity and National Branding from an Intersemiotic-multimodal Approach

Abstract

The Chinese film Wolf Warrior II floats all the way at the domestic box office, and jumps into the top 100 of the world's film box office rankings. It has achieved great economic success and ratings are overwhelmingly positive in China. Nevertheless, in stark contrast to this, Wolf Warrior II is cold at the box office abroad, and the word of mouth is not satisfactory. Transcreation is the re-creation or adaptation of content for a group of specific target audience. As an inter-related process of translation, a successful and holistic transcreation can arouse the same emotions as well as connotations produced in the target language as the source language. There are different perspectives to detailed translation analysis of China’s identity as a prominent character of contemporary society. Insofar as this research probes into the branding and in subtitle translation, it also constructs a binary theoretical model based on triadic signs of intersemiotic translation and metafunctional framework of multimodal analysis to testify China’s core values in this film and beyond.

1. Introduction

China, as a socialist country with its unique ideology and approach to international relations, has made significant efforts to promote its country and "made-in-China" products, including films that showcase China's image. This effort involves both internal and external considerations (Barr 2012:81) [1]. In the context of the film industry, this dichotomy is particularly important in understanding China's identity, as demonstrated in the film Wolf Warrior II. Translation researchers have taken a keen interest in studying how translation and transcreation in this film can contribute to China's national branding strategies, particularly in the cinematic context.

Under the roof of cultural globalization, it is becoming more and more imperative for different countries to compete and cooperate on the level of soft power. As a special cultural activity among people from different languages and societies, translation is an important way of cultural and ideological communication and naturally one of the key elements for the promotion of cultural soft power (Liu & Chen 2012:99) [2].

This globalized industrial chain has further promoted the portfolio of translation activities rather than pure code-switching project. Not a few translation agencies currently provide interpretation, multicultural marketing, multimedia/studio solutions, language and cultural training and other relevant services. The era where translators worked on translation materials without utilizing transcreation is no longer present. According to the statistics from Common Sense Advisory (2018), there has been a booming trend for the world’s language services industry as well as its market share. Figure 1 exhibits how this trend develops in the recent decade and beyond.

The global market for language services has experienced fast expansion, owing to the growing interconnectedness of the world. In the past decade, the market has grown twofold and was valued at 49.6 billion U.S. dollars in 2019. However, a prediction released in late 2020 projected that the language services industry would be slightly impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite this, the market was still expected to reach almost 52 billion U.S. dollars in 2020 and continue to expand in 2021 and 2022.

1.1. Transcreation

In 1987, Braniff Airlines ran a Spanish advertisement that turned out to be a major failure. The ad was meant to promote the airline's well-known tagline “Fly in leather” in English, but the anonymous Spanish translator responsible for the translation made a critical error, rendering the tagline as “en cuero,” which means “naked” in Spanish. This mistake was a significant misstep that cost the company potential Spanish-speaking customers, who likely opted to fly with other airlines instead of Braniff. If transcreation had been utilized in this instance, the translation would have been more carefully tailored to the target audience, leading to increased revenue and a more successful campaign. In recent translation studies, it is of particular significance for researchers and scholars to probe into new perspectives of methodology. Among these, transcreation is as an emerging term that has been a production from ‘translation’ and ‘creation’. Before translation researchers show their interest in transcreation, this concept has been discussed in business, especially the advertising adaption catering for target markets and customers.

For a long period, translation has always appeared as a kind of transformation activity compared with the source text, rather than a mimetic approach between two languages. By adapting itself with various circumstances of production and responses, translation draws attention from the target language culture and alienates itself from the source context. On the other hand, translation can show itself both in the two language settings with simultaneous production and reception.

A Brazilian scholar Harold de Campos initiates the term “transcreation” as a systematic methodology in his article (1963). Due to various untranslatable problems in the poems he deals with, he claimed that translation should follow the target of a parallel text beyond its literal meaning. However, this term has only been discussed in Brazil and India in the next three decades and very rare English dictionaries would like to welcome it. Two scholars, Juan Sager (1990) [3] and Maria Teresa Cabré (2003) [4] claims their pioneer researches to probe into this unknown field of transcreation. Sager (1990: 115) [3] insists that transcreation would offer a new perspective for translation regularization in situated contexts with more effective propaganda. Cabré (2003: 165) [4] expresses her astonishment when she is aware how much popularity of terminology before the 2000s and the term transcreation is suddenly reborn and revived in this trend. After almost two decades, this term and its connotation are still expanding in multiple disciplines and more transcreation scholars are involved in redefining its working definition in specific areas. In fact, it is imperative to check whether there is a majority of consensus of relevant studies among transcreation studies in the recent decade and seek for common ground to develop its regularization.

From two perspectives of adaptation and transcreation, Viviana Gaballo (2012) [5] performs a study in the analysis of accumulated works by scholars, translators and agencies to argue their internal relationship and choose from the distinguishing features among various approaches they follow through. Via reconfirmation of the etymological significance in transcreation, she divides the term into two parts, i.e. “translation” and “creation”, in order to further investigate the distinct characteristics from other frequently used terms with its new methodologies and solutions.

From multimodal semiotic approaches, Rike (2013) [6] attempts the convergence between translation and text output with transcreation assistance in intercultural communication. By quoting Alpha CRC and its tagline of transcreation service, she shows her insights for institutional educators and learners in translation quality assessment for major websites, marketing and advertising texts.

Denise Filmer (2014) [7] shifts her focus on interview among Italian correspondents for UK newspapers and the results are closely with the facts that untrained “journalator” are blamed for crucial political comments influencing target readers. Even though there are traits of transcreation, it is pending whether the unprofessional translators, or in other words the “journalators”, should take such responsibility in these tasks.

In another new media field of playwriting and actor’s lines, Christina Caimotto (2014) [8] observes Daniele Luttazzi, a famous comedian of Italy, who adapts some American counterparts’ works into his performance. From the perspective of satirical strategies used in the target culture, it is a pilot study of both cultural and political connotations to prove the function of jokes and shows how to apply transcreation to reach the equivalence from American to Italian culture, as well as shed similar light on Italian comedian lovers.

As a working definition used in this study, transcreation is a comprehensive concept in translation studies which combines the terms "translation" and "creation." This term refers to the process of converting a message from one language to another while preserving its original intent, style, tone, and context (Pederson 2017) [9]. A transcreated message should evoke the same emotions and convey the same meaning in the target language as it does in the source language. This process is similar to localization, which involves adapting a translated text to suit the target audience.

In the age of language diversification and information glocalisation, the development of translation is far beyond the word-for-word transfer and transcreation is becoming a buzzword in translation industry and studies. Under the background of localization, it is noticeable for transcreators to pay special attention to transcultural perspectives and renovate their communicative approaches catered to the target consumers in the scope of same functionality. According to its literary meaning, transcreation is the process of reconstructuring the whole source text to an adapted version that is more authentic and innovative. Despite of the translation marketing approaches, it is inevitable for translators to maximize the availability of materials in the etymological and intersemiotic meanings.

1.2. Identity and branding in translation studies

As for identity and branding in previous literatures, most of them are under the scope of business or relevant organizational settings. Rare scholars have made their steps in the field of translation. To embrace the criteria of transcreation in this article, the author would like to generalize the current researches on identity and branding, and shift focus on the perspective of culture and nation in the Chinese film and beyond.

Supporters of national branding often use metaphors to describe the market competition among different powers in the world and view branding as an effective strategy for balancing interests regardless of politics (Stock 2009; Pasquinelli 2010) [10, 11]. In their view, most scholars of national branding are focused on marketing and use a functional approach with few political paradigms. They consider identity and cultural traits as persistent and separate variables in establishing a national brand (Raluca-Gabriela 2013) [12]. However, some scholars are critical of branding and seek alternative solutions, such as "information capital" (Arvidsson, 2006) [13]. They argue that the discursive approach to branding is a renovated reiteration of neoliberalism with the assumption of a "universal mercantile republic" (Jansen 2008; Szondi 2008; Kaneva 2011) [14, 15, 16].

Research focusing on China has identified gaps in the application and redefinition of national branding in the country's new era, tracing back to its reform and opening policy in the 1980s, its entry into the WTO in 2001, and the Beijing Olympics in 2008 and beyond. Various scholars have conducted empirical analyses to provide critical perspectives on the effectiveness of national branding in China, including Loo and Davies (2006), Zhang and Zhao (2009), Scott et al. (2011), Fan (2014), and Wong and Liu (2017) [17, 18, 19, 20, 21].

As a country inherits its tradition of culture over 5,000 years, Chinese and their national identity and branding are composed of complex historical opportunities and choices. While among uncountable game changers in the long period, the modernity between 19th to 20th centuries is frequently mentioned as the golden time for China to modernize herself and becomes one of the developing countries. Through the test of New Democratic Revolution (1919-1949) and Second Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945), China forms a core value of nationality and coheres forward stronger after the establishment of People’s Republic of China in 1949.

In international and regional issues, China has played an active role in mediating its relationship with other countries. To fulfill this orientation, it is imperative for China to mobilize its collective efforts to improve competitive edges and brand itself with Chinese characterized images. In the age of globalization, national branding relies more upon soft powers rather than only with wealth and military power by initiative strategies of each country. This paper will work on the notion of national branding and identity via a semiotic analysis of the Chinese thematic film Wolf Warrior II from the transcreation and translation approaches.

1.3. Audio-visual translation and intersemiotic translation

When we look back at the trend of audiovisual translation, it is not hard to predict there will be a boom of its development in the coming decades. From the perspective of text types, the Bible and other literary translation works are the origins of translation. According to Roman Jakobson (1959) [22], interlingual translation, i.e., verbal textual translation, has remained as a focal point in translation studies. On the other side, he uses intersemiotic translation to analyze “verbal signs by means of signs of non-verbal sign systems” (Jakobson, 1959: 33) [22].

Before accepted as a member of translation studies, audio-visual translation has long been ignored and even discriminated for its semiotic characteristics. In previous studies, the kenning “constrained translation” is a popular term to indicate that translator’s efforts are constrained by other systemic components like paraphrase and adaptation in subtitle translation (Kelly & Gallardo, 1988) [23].

With a platform based on the full play of interaction and participation, inter-semiotic translation is a new perspective to probe into individual and communal bindings in cultural differentiations. As a certain group of interests, they suggest that the procedure of cooperative transition should be noted to reveal its influence on relevant communities or public scenes.

There is a pattern for translation act including a process of political and cultural orientation from source and target language approach to make an impact on both two aspects of original and recipient culture. When a textual translation applies pure verbal meaning strategies, it is usually taken as a process of intrasemiotic approach for its usage of verbal signs and meaning in the linguistic system. On the other hand, an inter-semiotic translation walks the source text through sign systems and builds proper bridges between cultures and media in different settings.

Compared to literary translation, translation from an inter-semiotic approach requires the translators to change their source-oriented thinking pattern to more exemplary paradigms. Among the many different channels of receiving and analyzing non-verbal information, translators could be a part of the process and intercede between source-target parties with re-created sense of meanings. As one of the co-founders of semiotics with Saussure (2011) [24], this paper builds its theoretical model from Peirce and his model of triadic signs.

2. Theoretical framework

Inspired by the widespread use of systemic functional linguistic (hereinafter referred to as “SFL”) multimodality in film subtitle translation, the theoretical framework of this paper will combine this approach with semiotic translation in analyzing cases in Wolf Warrior II. This paper will analyze some subtitling cases by selecting three metafunctional components as fundamental methodology in semiotic translation, including triadic signs of Charles Sanders Peirce (1991) [25], and Kress and Van Leeuwen's metafunctional framework (2006) [26].

Firstly, it is not hard to observe the three core elements in Peircean model: Representamen (or Sign), Object, and Interpretant. All the three terms are correlated with each other and interactive in the process of pragmatic communication. Here the researcher takes the representamen as a marker to represent a sound image, a word cluster, a facial expression or a series of dynamic stills that leading the signified concept. Figure 2 clearly indicates how the three components are connected and interacted with each other.

There is a triangle communication is among the three terms. A form is constituted from the representation of the sign to the interpretant. On the other hand, it can also be transferred from a particular object via a determination of the sign from the representation or the interpretant. In Peirce's view, the three aspects are not at the equal but fall into three levels. The representamen is first, the object second, and the interpretant third. Among them, the object determines the representamen, the representamen determines the interpretant, and the object indirectly determines the interpretation item through the signified medium. The representamen is passive when compared to the object, and the active relative to the interpretant. In other words, the object is the cause of the representamen, and the interpretant is the meaning of the representamen. By removal of the object, the representamen will no longer exist. When a representamen is associated with an object, the representamen is a variable and the object is a constant. When a representamen is associated with an interpretant, the representamen is a constant and the interpretant is a variable.

To be more specific, the representamen can be understood as a sign for a particular item. For example, we can use an utterance “Mona Lisa” to signify the famous portrait by Leonardo Da Vinci. The object, on the other hand, is what the utterance indicates as an entity or attachment, i.e., the portrait Mona Lisa and its function of beauty and elegance modeling. Interpretant is the subjective perception from different people. If someone looked at the famous portrait and claimed that it could be a man disguised in a woman attire. In this case, Interpretant may not be popular among the potential audiences thus it needs to be further discussed.

After that, Kress and van Leeuwen's metafunctional framework is also workable for this paper because there are not only the language strategies analysis, but also more in-depth semiotic studies on both verbal and visual materials. Based on Halliday’s theory, there are three major functions of systemic communication, which are being ideational, interpersonal and textual. Kress and van Leeuwen then replace the three previous functions with new ones as being representational, interactive and compositional. Figure 3 indicates the new structure and its internal working mechanism.

Under the roof of representational function, processes, participants and circumstances form a unified whole family with different purposes. Processes perform as the matters symbolised in a clausal structure via verb phrasal application. Participants are not only confined to homo sapiens but also any entity would be a part of the process, usually in the form of noun phrases. Circumstances provide information of relevant but rather secondary knowledge in the process, like time, place, venue and so on. Interactive meaning is composed by contact, social distance as well as attitude. Contact here indicates the observers acquire the connotation of image through interaction in the context. The definition of social distance is variated by the two scholars among participants in the depictive settings. Whether near or far, the material distance determines the communicative efforts between source images and potential viewers. The shorter distance could lead to a closer intimacy among the audiences. At the bottom, there is the composition to correlate with the other two functions of representation and interaction. The first value is information, which allows the viewers and syntagms interrelate in a particular part of the image. Salience, including the products from participants and other syntagms, plays a role in analysis of images through the realization of various factors as foreground and background, color comparison, sharpness variation, and so on. Finally, framing is influential on the image in forecasting their allocation and grouping according to meanings.

Based on the transcreation and subtitle translation in a mainstream film full of Chinese characteristics, this paper aims to outline the two frameworks and pack into one analytical model in the following case studies. Figure 4 exhibits this integrated mind map and its correlational operating principles.

The figure 3 above reveals the general working mechanism between two different mixed modes, i.e., the verbal intersemiotic approach and visual multimodal approach. The potential analytical medium is the dynamic frames or shots in the chosen film. Through the triadic interaction in the semiotic contexts, deep analysis will probe into the connotative relations with various significations. On the other hand, since there are many visual aids in films along with lines, it is rational to combine representational, interactive and compositional metafunctions of each frame. Under the roof of this combined theoretical house, cases on subtitle translation, as well as transcreation, will be analyzed beyond the textual level and a conceptual bridge created to a branding and identity analysis.

3. Case study

As the follow-up sequel of Wolf Warrior in 2015, the film hero Leng Feng came back to China with his comrade’s remains. What spoils the funeral is a boss from a demolition crew who urges his men to have a mandatory dismantling of Leng Feng’s house. Infuriated by his violence and threatens with gun shooting, Feng kills him in front of the police, and is sentenced to a military prison for two years.

Since his fiancée Long Xiaoyun is missing three years ago, a bullet has been with Feng as a keepsake and clue. He goes to Africa upon completion of a sentence to escape from his previous life. Employed as a mercenary by a local freighter, Feng beats and defeats a group of pirates to avoid an undeserved disaster. One day when a group of insurgent troop attack them, Feng and his local partners put up a strong resistance against the rebel forces. To rescue the Chinese war refugees, a fleet from China arrives and one Chinese businessperson in the country tells Feng that his bullet might have stories with a group of European rebel mercenaries in this civil war.

Then after, Feng volunteers to rescue Dr Chen who endeavors his great efforts in a new vaccine for a local fatal disease. Unfortunately, Dr Chen is killed by anti-government armed force before Feng arrives. Together with a doctor Rachel, and a little girl Pasha who has virus antibodies, Feng save them from the destroyed hospital and move to a Chinese factory called Hanbound owned by Yifan. While the head of mercenary army “Big Daddy” desires for the vaccine formula, he diverts his attention to Pasha and attack the factory with his gangsters. Through arduous struggles, the team led by Feng and factory security captain Jianguo repulse the enemy and killed “Big Daddy”. At the end of the show, Feng rescued his Chinese crew back to their motherland and he was enrolled back to his squadron with this honor.

Although there are different opinions of praise and abuse, this film has been a box office winner. Figure 5 explains in details about its performance according to Box Office Mojo.

As a professional website focusing on world’s top film box office return, ranking in Mojo is widely accepted throughout the film industry as a key reference to value various cinematographic works. Numbers in this chart above indicate that Wolf Warrior II is one of the top foreign language films to the American market. While receiving ice baths in American market, it is phenomenal in Chinese box office and rated high among Mainland Chinese.

Nevertheless, according to the BBC news (2017), one famous tagline in the film was translated as "Anyone who offends China will be killed no matter how far the target is" (犯我中华者虽远必诛). Due to this unequal and inappropriate translation, many western audiences become doubted and even worried about Chinese mainstream thoughts and politics. Inspired by this misunderstanding and even more conflicts caused by such irresponsible translation, this article aims to have a comprehensive analysis on coping transcreation under the perspective of cultural identity and national branding in China.

For the data collection, the author selects 31 shots of subtitles from 11 instances of Wolf Warriors II according to the storyline and timeline to carry each analytical study. Even though this film is a coherent work without too much contradiction from beginning to the end, there are still prearranged criteria before each shot is chosen in the corresponding case analysis.

- The chosen subtitles and their translation should be mixed with both visual and verbal approaches.

- At both lexical and functional levels, particular expressions will be analyzed to distinguish their common ground as well as discrepancy.

- From the preliminary verbal and visual analysis, cases and their connotation could be taken into the scope of branding and identity discussion.

3.1. Findings

3.2. From translation to transcreation: an intersemiotic-multimodal approach

The increasing awareness of translators in applying semiotic and multimodal approaches has witnessed a change of translation from meaning deliverance to cultural introspection among intra-linguistic contexts in recent decades. In the age of theoretical and practical translation convergence, it is beneficial to introduce transcreation as a new beam of light for translators to mobilize their initiative and creativity and build a more communicative intercultural approach between source and target context. In the film Wolf Warrior II, there are abundant modes from either “visual and acoustic modes of signification, as well as different graphic sign systems” (O’Sullivan, 2013) [27].

In this case, it is not only an analytical process on textual level and imaging counterparts for implicative meanings and significations. In the chosen instances, six components in the previous model will be discussed: visual frame, body language, background sound effect, signification and metafunction. From this perspective, there will be a textual translation analysis of on the specific instance according to the self-proposed criteria above mentioned.

Instance 1(Screenshot at 03:57)

@2017 CMC Pictures

Source text (ST): 所有人躲避到舱里

Target text (TT): Get everybody below deck!

At the beginning of this film, there is a hijack happening to a merchant marine in Africa. While the captain urges everyone back to the deck below, Feng Leng, the former wolf warrior, recklessly jumps into the water to combat with the bandits. By wearing simple casual clothes in light color, Feng makes himself a sharp contrast with the blue sea with grand background music to symbolize it could be another mission impossible for him. In this situation, Feng is portrayed as a signification of bravery and object of Triadic Signs can best describe this scene. In Chinese, there is an imperative tone and the target text keeps this pattern. This weakened tone in English may not well convey the urgent situation but it is open to debate whether the English version should change the action initiators from everyone in danger to somebody else in charge.

Instance 2 (Screenshots at 7: 38 and 7:41)

@2017 CMC Pictures

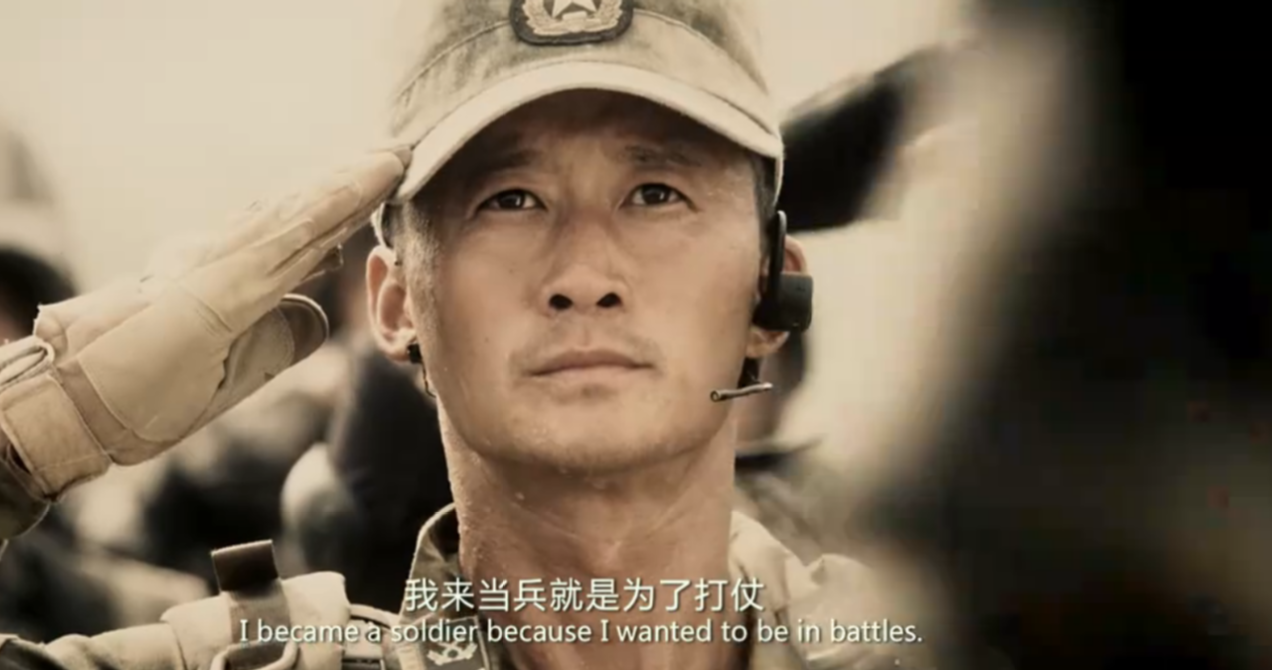

Source text (ST): 队长: 告诉新来的,俺们中队的座右铭是啥啊(图1)

大飞: 我来当兵就是为了打仗(图2)

Target text (TT): Captain: Tell these rookies what our motto is. (Shot 1)

Da Fei: I became a soldier because I wanted to be in battles. (Shot 2)

In the midst of the forced demolition in his dead comrade-in-arms community, there is a series of scenes in recollection mode. Plots from the previous Wolf Warrior bring the audience with the voice of Da Fei, the sacrificed soldier in a mission. In the first screenshot, the captain is seriously staring the new enrolled wolf warriors together with other veterans, including Feng. On the representative of the captain, a soldier is shouting loudly and wildly to the rookies. Then everyone answers with the words “being humble”. While Da Fei replies his thought in the second shot with image of Feng’s salute after Fei’s death. The tense is more mixed with nerve, sorrow and solidarity with a bugling melody. As the interpretant of respect for Fei’s devotion to the country, this salute of Feng indicates his sense of responsibility and belonging to his Wolf Warrior squadron with interactive attitude. The Chinese source text by captain applies a humorous way with dialectal and adjective possessive pronoun and English version neutralize this feature with a simple “our”. The audience may easily understand this adaptation. On the other hand, the deverbalization also slightly distorts the original meaning and tone. What Fei’s response should be dealt carefully since a literal translation may cause uneasiness of target audience to think China as a brutal country in educating soldiers as a battle maniac. In this case, “打仗” can possibly be toned down to “protect my country” for a substitution.

Instance 3(Screenshots at 28:50, 28:52 and 28:54)

@2017 CMC Pictures

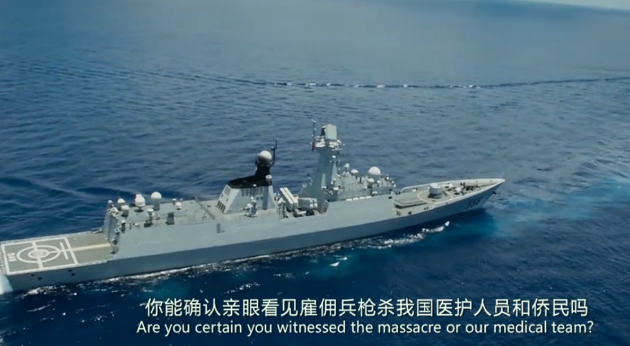

Source text (ST): 字幕:南印度洋中国海军编队接收到中央军委命令立即赶

赴非洲执行撤侨命令(图 1)

旁白: 他国战舰已经全部驶离战斗区(图2)

旁白: 我们还要继续进港吗(图3)

Target text (TT): Subtitle: South Indian Ocean. Redeployment of China Navy

Fleet to Africa for evacuating mission by Central Military Commission (Shot 1)

Voiceover: All foreign vessels are leaving the war zone. (Shot 2)

Voiceover: Are you certain about docking? (Shot 3)

After the rebellion forces begin to attack civil targets, Chinese government begins to send a fleet to rescue overseas compatriots to come back to China. In a grand view, three warships with Chinese national flag as their identity are sailing on the ocean in their formation. This signification of object can easily bring audience to a battle prelude. A military batman voices over the second and third chosen shots. In Shot 1, the source text is employing a complex sentence structure with multiple verbs and English version is naturally simplified with nominalization and phrasal structure patterns. It is notable that in Shot 2, the sentence tense changes from a present perfect to present progressive. Disordered logic and even misunderstanding may happen to translation researchers here to identify this translation purpose. As for the last shot, it is contradictory to use a questioning sentence to the commander from the standpoint of a batman. The removal of personal pronoun with inanimate subject would outweigh the previous translated version in this sentence.

Instance 4(Screenshots at 32:37, 32:48, 32:50)

@2017 CMC Pictures

Source text (ST): 大使:此次撤侨行动,事关重大(图1)

长官: 必须要一个人单独完成任务(图2)

士兵: 干什么的(图3)

Target text (TT): Ambassador: This operation is highly important (Shot 1)

Commander: Someone has to undertake the mission alone. (Shot 2)

Soldiers: What’s your purpose? (Shot 3)

Amongst the heated debate between the Chinese ambassador and commander in evacuating strategies, they express their own concerns separately but reach a consensus of sending someone alone to rescue Chinese refugees. Feng volunteers himself as usual but two soldiers stop him before his approach. Close-up views are intertwined to sensationalize the urgent situation by depicting both of their facial expressions along with loud voices. It is functional in concise translation sentence structure in both shots. As a viewer and an interpretant role in this scene in the debate, Feng soon figures out the dilemma and devotes himself in the mission impossible. The controversial translation appears in Shot 3, the film gives a whole scene and two soldiers are stopping Feng as an unauthorized person. When people use “干什么的” in oral Chinese, the function of intimidation and interception is more overwhelming than the other purposes. In the target text, “what’s your purpose” is too much bookish for military to use and it is far contrary to the compositional function of information value and framing. It is better to use a straightforward “on your feet” in this case.

Instance 5 (Screenshots between 48:26 and 48:30)

@2017 CMC Pictures

Source text (ST): 你能对你说的话负责吗 (图1)

你能确认亲眼看见雇佣兵枪杀我国医护人员和侨民吗 (图2)

Target text (TT): Do you stand by what you’re saying? (Shot 1)

Are you certain you witnessed the massacre of our medical team? (Shot 2)

After the touch-and-go rescue of Rachel and Pasha, Feng reports to the commander about what he witnesses in the hospital. This irritates Chinese command center but the commander keeps his hair on and repeatedly asks Feng whether what he reports is true or not. It is quite eye-catchy for Shot 1 since all military staff are in same uniforms and all other batmen are shifting focus from their chores to the commander. This body language clearly indicates that interpretant of Feng’s informative signification is quite shocking to the Chinese navy. It is a progressive strategy for the commander to ask Feng with intensive structures and tone.

As for the translation, the first shot needs to be more concise to make a larger contrast between the second. In this way, the object clause “what you’re saying” could be replaced by “your words”. To convey more faithfully and comprehensively, the second shot may be considered to revise as follows: “Are you in person certain about the mass shooting at Chinese medical team and emigrants?”

Instance 6 (Screenshots at 49:49, 49:53 and 51:14)

@2017 CMC Pictures

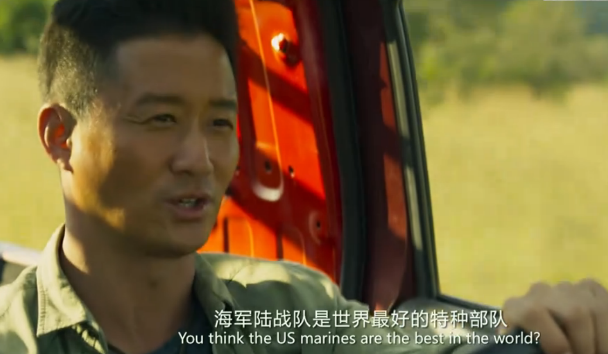

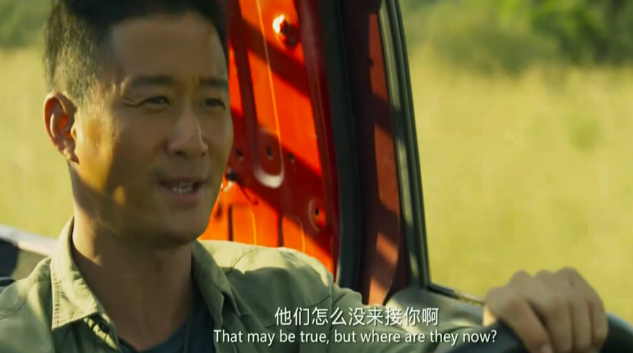

Source text (ST): 海军陆战队是世界最好的特种部队(图1)

他们怎么没来接你啊(图2)

海军陆战队接你来了(图3)

Target text (TT): You think the US marines are the best in the world? (Shot 1)

That may be true, but where are they now? (Shot 2)

Your GIs are here to get you. (Shot 3)

On the way to the factory, Rachel has a quarrel with Feng for the reasons why US government does not help her. Feng plays with a military cynicism on US marines and it irritates Rachel soon. She is about to leave Feng only if she witnesses several lions are lingering around them. From the semantic level, Feng applies an ironical approach to remind Rachel of the real savior for her and expresses his disdain on the American military counterparts. Between Rachel and Feng, they do have a completely opposing image on US marines as an interpretant. This part could lead to some resentful feedbacks from American viewers while things may be completely different among Chinese audience. Feng’s words are even meaner with his scornful facial expressions and teasing tone for Rachel to accept. Moreover, what brings Rachel back is the hopeless African wilderness with the threatening unknown animals and mercenaries. In the translation, it is quite creative for the English version to be coherent and humorous similar to the source text. The highlight is in Shot 2 while the target text adds extra information of Feng’s opinion, “that may be true”. This reflects his confidence and independence as a Wolf Warrior. Diction in the last shot is also varied from US marines to GIs. GI, or Government Issue, is a popular term among Americans to call their troops despite of services. In the shot, it is redundant to repeat the previous word “US marines” to call these lions because Rachel has been annoyed by this teasing. A creative diction can signify Feng’s humor, generosity and responsibility as a Chinese army man.

Instance 7 (Screenshots at 58:58, 59:03 and 59:22)

@2017 CMC Pictures

Source text (ST): 冷锋:老师傅(图1)

何建国:你也不错(图2)

冷锋:班长好(图3)

Target text (TT): Feng Leng: Old timer. (Shot 1)

Jianguo He: You’re not bad yourself? (Shot 2)

Feng Leng: At your service. (Shot 3)

This is one of the few scenes of a relaxing situation in the film. Right after the announcement of evacuation plan for everyone, African and Chinese refugees are throwing themselves in an open-door party. Feng and Jianguo are rambling on the terrace with their military career. At first, Feng attempts to ask Jianguo’s history in a familiar tone as if they are old pals by calling him “old timer”. This soon becomes an icebreaker and they share their previous military identity with mutual respect. By knowing Jianguo used to be a senior special forces member, Feng salutes at this veteran in front of him with admired smile. The setting of this scene is in a joyful night and two heroes in the film are given conversational close-ups. While they are both in their green military-like uniforms, Feng is holding an off-painted enameled cup carved with former Chinese Chairman Mao Zedong’s quote: 为人民服务(Serve the people). This object is served as a modeling of expected soldier image in China. Translation here symbolizes an institutional conversation between two army men. Misunderstanding may happen to non-native English speakers for old timer could be misinterpreted by someone. There could be alternative solution for Shot 2 because the English version is not so equivalent to the source text and the context. Compared to the response to “old timer”, “you are also a badass dude” may better express the appreciation and bonded military relations between Jianguo and Feng. In the last shot, “班长” is omitted in the target text as “squadron leader” or other terms. As a punchline, it could be easier for the audience to distinguish the feelings out of the form in the part.

Instance 8 (Screenshots at 01:08:54, 01:08:57, 01:48:20 and 01:48:22)

@2017 CMC Pictures

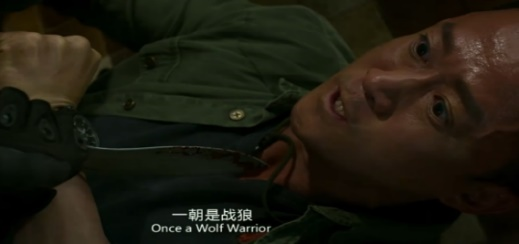

Source text (ST): 一朝是战狼II(图1)

终身是战狼II(图2)

血债(图3)

血偿(图4)

Target text (TT): Once a Wolf Warrior (Shot 1)

always a Wolf Warrior! (Shot 2)

Blood... (Shot 3)

for blood. (Shot 4)

In the fighting scenes of this film, Feng’s identification of “Wolf Warrior” is constructed mainly through his bravery struggle against mercenaries. These four shots are also available on the film posters throughout Chinese cinemas. As the core value of this film, loyalty, perseverance and revenge are visible features from Feng and beyond. Similar paralleled structures are in the two fighting scenes with the symbolic facial expression of Feng. Accompanied by drumbeat music, the lines are cues and clues of seeking the inner self of the wolf warrior. The translation also follows the original sentence patterns and similar expressions can find their counterparts between two languages. In the subtitling, the film splits the two complete short sentences into two parts and each one is in a progressive climax approach. Viewers can observe this Wolf Warrior representamen from Feng and think about its deep meaning.

Instance 9 (Screenshots between 01:45:43 and 01:45:44)

@2017 CMC Pictures

Source text (ST): 士兵:我们得到上级命令(图1)

长官:开火(图2)

Target text (TT): Soldier: We’ve received orders from COMMAND! (Shot 1)

Commander: Fire! (Shot 2)

Besides the fighting scene of Feng, the navy commander in the film is another important character who affirmatively promotes the plots to a Chinese heroic epic in the end. While Big Daddy and other insurgent troops attack the factory and slaughter Chinese civilians, Chinese army is still anxiously standing by the orders from command. When the order finally arrives, a soldier is holding the command in a pious gesture with hands and arms wide open to the commander. He is trying to read the command in details but is interrupted by the commander suddenly with a shouted “Fire”. His tears in the eyes are reflecting his anger and grief as a Chinese to witness such an outrageous action. From his roaring facial expression, the extreme feeling of rage and resolution turns into the final order according to the close-up in Shot 2.

Here it is crucial to understand the background and atmosphere in the command room. The anxiety, sorrow and resentment are fermenting among the navy. Translation of “上级” is capitalized in the English text and marked as a symbol of collective authority or legality to launch the attack. If “superior” or “higher authorities” were used, viewers would be lost in deciding who is the specific figure or institution to make such a crucial command. From the cultural aspect of Chinese society, the power and status of higher-ups typically stem from their rank and expertise, rather than solely from their individual capabilities. Lower-level employees are expected to show them deference, as well as comply with their directives. However, superior leaders also have an obligation to take an interest in the work and personal lives of their subordinates and offer them aid and backing when needed. in the Chinese military context, the influence of these superior leaders stems from their positions and ranks within the military, making their authority generally unquestionable.

Instance 10 (Screenshots 1-5 01:50:29-01:50:50; Screenshot 6 01:50:30)

@2017 CMC Pictures

Source text (ST): Big Daddy: You’re gonna die for these people (Shot 1)

Feng: I was born for them. (Shot 2)

Big Daddy: People like you will always be inferior (Shot 3)

Big Daddy: to people like me. (Shot 4)

Big Daddy: Get used to it. (Shot 5)

冷锋:那他妈是以前(图6)

Target text (TT): 老爹:没错,你将会为这些人而死(图1)

冷锋:我就是为他们而生的(图2)

老爹: 这个世界只有强者和弱者(图3)

老爹:你们这种民族永远属于弱者(图4)

老爹:你要习惯(图5)

Feng: That’s fucking history. (Shot 6)

This is adapted from the final fight between Feng and Big Daddy. After they exhaust their ammunition, there is a fight at close quarter in front of other Chinese refugees trapped in the factory. This has been an evenly matched combat until Big Daddy hits below the belt with knives. Feng is severely injured with blood and brought to a corner close to the refugees. Big Daddy starts to humiliate Feng along with the crying and begging people. The conversation from Shot 1 to 5 is in English and Big Daddy clearly steals the thunder. Right before Shot 6, Feng rises up and fight whatever it takes against Big Daddy. Then he punches the villain into death and says the swearing words to his body. In translation, Shot 1 to 5 are not in a total equivalence with the source texts. In Shot 1, an emphatic term “没错” added to enhance the teasing tone of Big Daddy right near the exhausted Feng. Nevertheless, it is more formal when the Chinese “将会为这些人而死” varies the colloquial form of English. A referential version could be “没错,你就是因为他们而死” and it is more coherent with Shot 2 and its translation. In Shot 3 and 4, two parts of one single sentence are divided in line with storyline evolvement. To better explain separately, it is necessary to rearrange the sentence order and Shot 4 in the target text is actually the translation of Shot 3 in source text. Shot 3 in the target text is an overgeneralization for the semantic meaning. Maybe another paralleled structure can be considered and translated as “我们民族永远是强者” and simplify Shot 4 to “你们民族永远是弱者”. In Shot 6, swearing words appear firstly in the film to represent the repressed emotion of Feng. Even though it could lead to a heated discussion whether that is excessively much nationalism, the translation sticks to the original style and acts its role in the target context.

Instance 11 (Screenshots at 01: 54: 52, 01:54:25)

@2017 CMC Pictures

Source text (ST): 把国旗给我(图1)

开车(图2)

Target text (TT): Pass me the flag. (Shot 1)

Drive. (Shot 2)

At the end of the film, the refugee motorcade drive through the war zone between government and rebellion troops. To avoid unnecessary casualties, Feng urges others to find him a Chinese national flag and hoist the flag with his arm. The gunfire ceases shortly to let them pass to show mutual respect from both warring sides for the selfless Chinese dedication to this country and its people. The hopeless refugees and determined Feng make a sharp contrast in the scene. It is a sign of Feng to change from an individual warrior to a national symbol when he is an integral part of the Chinese national flag. For Shot 1, it is debatable whether “flag” should be with a qualifier “national” to avoid ambiguity.

3.3. From transcreation to branding and identity: how China performs in and out of scene?

As an indispensable part of cultural products like films in overseas promotion, voices of recipients must be heard to reach a theoretical “Horizon of Expectations”, namely the sociopolitical, cultural and aesthetical baggage of the audience which is based on historical contexts, previous readings and the ‘opposition between fiction and reality’ that construct the audience’s expectations (Jauss, 1982:25) [28]. In the reading activity, it is opposite from recipient to the horizon of expectations and the objectification of the cultural product would be accepted under a transcendental experience and aesthetics. In a word, the completion of the art reception activities can only process and finish with the mutual chemistry of the objectification and materialization. As far as the subject is concerned, this form of synchronicity occurs in the reading process endowed by diachronicity and it is the objective existence beyond the subject itself. To be brief, the known horizon of expectations for appreciative recipients is quite a vague and complex concept, containing many factors like education level, personal life experience, and aesthetic taste. On the next level, it is related with his or her intertextuality experience in similar or different cinematographic works. In addition, another noticeable conceptual pillar is the recipient’s mastery degree of the relevant program and convention in an artistic category, such as era, nationality and cultural environment in which the viewer is influenced on art taste and interest. This term is later adapted to the cultural communication field of film industry. With this trend in mind, overseas acceptance of Chinese film is also the process and result of the interaction between overseas audiences and the film works. In short, what and why does the audience want to watch in the film?

Patriotism and heroism are the spiritual core of Chinese military films. The test of life and death on the battlefield gives the Feng an unusual perseverance, especially the main characterization in the real war environment and the enemy and the choice between life and death to show the heroic and tenacious battle of the contemporary soldiers. Wolf Warrior II embodies the patriotic tradition based on the aesthetic spirit of realism. In mainstream Chinese films, especially war and martial arts action films, the theme of excluding the enemy, defending the country, and defending the national dignity has always existed. In addition to many audiovisual elements and cultural elements suitable for contemporary audiences, there are two doctrines in Chinese traditional culture adopted in this film: one is the Confucian approach of obedience, and the other is the Legalist method of competition. The story is also a grand narrative of fighting for China under its peaceful rise. From the perspective of aesthetics, the film is a fine work of contemporary Chinese soldiers with ideological pursuit and artistic taste. The film is about patriotism or a positive expression of the national sentiment of the country.

Wolf Warrior II also reflects a heroic Chinese film tradition based on the spirit of traditional culture. Feng is not only a soldier defending national dignity, but also has his own personal attachment with Long Xiaoyun, his missing fiancée. It has rewritten the cruelty of the war in another way. The film is good at the expression of the main theme and the balance between "big" and "small". The so-called big military is responsible for defending the country and the small is personal feelings. Wolf Warrior II has created a modern Chinese soldier image that is both masculine and "human". Regarding the characteristics of "human", the recipe for success of the film lies in the hero of the military theme. The physical property is reduced to humanity. In the previous works of art, the "military people naturally obey orders" discipline often pictures the military as by-products of power. In this setting, the characters would appear very dull and blunt. On the other hand, the characters of this film are very vivid, especially Feng, with flesh and blood.

Against the backdrop of global cooperation and conflict, what is intriguing is the metaphorical expression of China-Africa relations. Obviously, the film shows a strong sense of Chinese superiority in China-Africa relations. In contrast with riots, poverty and hunger in Africa, China is still their savior and shelter with the signification observed from Feng Leng. The interesting plot setting is that both Feng and Dr Chen have African children as their adoptive children. They both call the Chinese "Godfather" or “Gan Die” in Chinese Pinyin. Even in traditional thought, we only call people Godfather when the person baptizes us, but this film makes this term more secular. In this way, the Africans in the film are very respectful and friendly to China. Chinese are highly evaluated even by the insurgents and they usually can have the privilege to survive from the civil war. The climax is that when Feng holds up the Chinese national flag, the motorcade crosses the bonfire line safe and sound. At the end of the film, there is a huge Chinese passport bearing a slogan to symbolize a strong Chinese play in the international arena.

Although the construction principles and narrative logic of national image and identity in the Wolf Warrior II are based on the rise of China with its great powers. However, as a cultural product, the film, as a component of the Chinese soft culture, is not only for the Chinese audience, but also for one of the international cultural products. In this regard, the film seems to be too overbearing with the character setting of an African savior. It is arbitrary to judge China-Africa relationship in such a preconceived mind. The mercenary's wickedness is also unclear, and "evil" has no reason and it is too simplistic. Based on the translation analysis in previous parts, the expression of patriotic sentiment is often too direct and eulogistic. Such a nationalist stance is not conducive to the overseas promotion of this film and bilateral relationship with Africa. In the author's view, the construction of the national image must not only express the strength of the rise, but also be restrained, neutralized, and keep a low profile. Films can express nationalism sentiments, national consciousness, and patriotism, but they must also have all human consciousness, global identity, and universal values.

The reason why War Wolf II can evoke the patriotism of the Chinese people is because in a war-torn country in Africa, China dispatched warships to quickly evacuate overseas Chinese, effectively protecting the personal safety of Chinese citizens. This is true in the film as it is adapted from real life issues. In the Libyan war and the Yemeni civil war, the Chinese government sent warships and military aircraft to safely evacuate tens of thousands of Chinese refugees at the fastest speed. It is from this kind of real protection that the Chinese people naturally have a passion and gratitude for the motherland. However, if the country neither protects the safety of citizens nor promotes the welfare of citizens, then it will not only not get people's love and support, but will only cause disappointment, contempt and even hatred. A black humor in the film is that when the female lead American citizen Rachel hears that US warship is evacuated, she calls the US Embassy to ask for help and cannot get a response. In the film, scream and swear are her only responses to her country. However, in real life, it is also quite guaranteed of the US government to protect its nationals in warzones.

For the source of patriotism, we must ask a series of questions before we delve into a further discussion. Is it a temporary expedient or a permanent solution for the protection of personal safety and welfare? Is it an instinctual emotion born of the situation, or a clear legal responsibility for everyone to abide by? It should be said that different countries have different answers. If it is a feudal authoritarian country, because the power is a family-oriented type and privately owned by a person, it is clear that the country does not assume the responsibility and obligation to protect its citizens and to promote universalized personal welfare. It only protects the safety of privileged class and all others can only wait for the reward from the supreme. If it is a modern democratic country, sovereignty and power belong to the people, such as the provisions of Article 2 of the Constitution of the People’s Republic of China. The responsibilities and obligations are legal and cannot be violated. Citizens can express their love and gratitude to the country. However, the country has no power to force citizens to ask citizens to be grateful to its governance. Of course, the country has the right to require citizens to understand the history and culture to maintain national security and form a strong national identity. Not only that, but if the state does not fulfill its responsibilities and obligations to protect citizens, or does not perform well enough, citizens have the right to make recommendations and comments on the state. It is not allowed to criticize your own country and government. It is certainly not a government that serves the people. It is certainly not a country and a government in the modern democratic sense.

Moreover, in modern democracies, citizens must perform their own civic duties while enjoying national protection and state welfare, such as obeying laws, paying taxes, and serving military obligation. In this way, the relationship between the country and the individual is a two-way reciprocal relationship: on the one hand, the country exists for the sake of citizens, and it is necessary to actively protect the safety of citizens and enhance personal welfare; on the other hand, citizens must fulfill their civic obligations and strictly abide by them. National interests and personal interests are protected by the same laws and are inviolable. Therefore, it is not possible to harm national interests and public interests in the name of personal interests. Similarly, the act of infringing and trampling on the interests of citizens in the interests of the national interest or the public interest is also illegal. As the shocking picture at the beginning of Wolf Warrior II reveals: the act of smashing the family housing of the martyr is what the underworld does, and of course it is illegal and humiliated to the bereaved. Discussion of the new relationship between the state and the citizen under the modern democratic system should be considered from the perspective of the source of the power of modern democratic countries. In fact, the legitimacy of modern democratic countries comes from the consent, recognition and empowerment of all citizens. In other words, the country is the result of collective consent and contracting by citizens. Furthermore, state power is generated by citizens who give up part of their rights. Each of us is born with inviolable sacred rights, such as the right to life, property, and freedom. The reason why people form a country is to better protect and realize these sacred rights of the individual. The authority of the state derives from both civil rights, so it needs to be supervised and restricted by civil rights.

4. Conclusion

This paper explores the use of triadic signs from intersemiotic translation and a metafunctional framework from multimodal analysis to investigate the effectiveness of verbal communication and translation when supported by visual explanation in transcreation. The study includes a timeline case study of selected instances from War Warrior II to observe subtitle translation and identify intercultural gaps between China and other countries. Given the film's reliance on visual imagery, the paper constructs a model to provide a more comprehensive analysis of audiovisual translation studies, which have traditionally focused only on static stills. Additionally, the paper examines the cultural implications of transcreation, specifically in relation to issues of identity and branding. The discussion of these topics is informed by the theory of the horizon of expectations and considers the broader implications of transcreation beyond individual characters to national identity.

References

- Barr, M. (2012). Nation branding as nation building: China’s image campaign. East Asia, 29(1), 81-94.[CrossRef]

- Liu, M, & Chen, S. (2012). On translation and cultural soft power. Foreign Language and Literature, 28(4)99-102.

- Sager, J. C. (1990). Practical course in terminology processing. John Benjamins Publishing.[CrossRef]

- Cabré Castellví, M. T. (2003). Theories of terminology: Their description, prescription and explanation. Terminology, 9(2), 163-199.[CrossRef]

- Gaballo, V. (2012). Exploring the boundaries of transcreation in specialized translation. ESP Across Cultures, 9, 95-113.

- Rike, S. M. (2013). Bilingual corporate websites-from translation to transcreation.

- Filmer, D. (2014). Journalators? An ethnographic study of British journalists who translate. Cultus, 7, 135-158.

- Caimotto, M. C. (2014). Transcreating a new kind of humour: the case of Daniele Luttazzi. Cultus, 158-179.

- Pedersen, D. (2017). Managing transcreation projects: An ethnographic study. Translation Spaces, 6(1), 44-61.[CrossRef]

- Stock, F. (2009). Identity, image and brand: A conceptual framework. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, 5(2), 118-125.[CrossRef]

- Pasquinelli, C. (2010). The limits of place branding for local development: The case of Tuscany and the Arnovalley brand. Local Economy, 25(7), 558-572.[CrossRef]

- Raluca-Gabriela, Z. (2013). The Role And Importance Of Public Diplomacy, Romania Case Study In The Context Of Integration Into Nato. European Scientific Journal, ESJ, 9(19).

- Arvidsson, A. (2006). Brands: Meaning and value in media culture. Routledge.[CrossRef]

- Jansen, S. C. (2008). Designer nations: Neo-liberal nation branding–Brand Estonia. Social identities, 14(1), 121-142.[CrossRef]

- Szondi, G. (2008). Public diplomacy and nation branding: Conceptual similarities and differences. Netherlands Institute of International Relations" Clingendael".

- Kaneva, N. (2011). Nation branding: Toward an agenda for critical research. International journal of communication, 5, 25.

- Loo, T., & Davies, G. (2006). Branding China: the ultimate challenge in reputation management. Corporate Reputation Review, 9(3), 198-210.[CrossRef]

- Zhang, L., & Zhao, S. X. (2009). City branding and the Olympic effect: A case study of Beijing. Cities, 26(5), 245-254.[CrossRef]

- Scott, N., Suwaree Ashton, A., Ding, P., & Xu, H. (2011). Tourism branding and nation building in China. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 5(3), 227-234.[CrossRef]

- Fan, H. (2014). Branding a place through its historical and cultural heritage: The branding project of Tofu Village in China. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, 10(4), 279-287.[CrossRef]

- Wong, T. C., & Liu, R. (2017). Developmental urbanism, city image branding and the “Right to the City” in transitional China. Urban Policy and research, 35(2), 210-223.[CrossRef]

- Jakobson, R. (1959). On linguistic aspects of translation. On translation, 3, 30-39.

- Mayoral, R., Kelly, D., & Gallardo, N. (1988). Concept of constrained translation. Non-linguistic perspectives of translation. Meta: journal des traducteurs/Meta: Translators' Journal, 33(3), 356-367.[CrossRef]

- De Saussure, F. (2011). Course in general linguistics. Columbia University Press.

- Peirce, C. S. (1991). Peirce on signs: Writings on semiotic. UNC Press Books.

- Kress, G., & Van Leeuwen, T. (2006). Reading images: The grammar of visual design (2nd ed.). London/New York: Routledge.[CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, Carol (2013), “Introduction: Multimodality as Challenge and Resource for Translation”, The Journal of Specialised Translation, 20, pp. 2-14.

- Jauss, H. R., & De Man, P. (1982). Toward an aesthetic of reception.

Copyright

© 2025 by author and Scientific Publications. This is an open access article and the related PDF distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Article Metrics

Citations

No citations were found for this article, but you may check on Google ScholarIf you find this article cited by other articles, please click the button to add a citation.